|

Canada's

|

|

Today's amusement areas in Canada have their roots in the nature parks of the 17 and 1800s. Although some early Canadian parks began as religious campgrounds, most started as pleasure gardens and picnic grounds. Some of those were private but eventually opened to the general public. Other amusement parks grew out of sports fields and public bathing areas such as beaches and community pools, or some combination of all the above. The first of these began in the late 1700s through the 1840s in various parts of what would become today's Canada. They developed into amusement areas as more of the general public discovered them and gradually came to want greater variety with what was being offered.

Entrepreneurs saw an opportunity to make money by providing lodging, entertainment, refreshment, and diversion at these already-popular locations. As these were generally public (read: family) areas, the diversions provided were wholesome ones such as water slides, hiking trails and pony paths, or sports competitions in the form of friendly foot or bicycle races, horseshoes, quoits (a kind of ring toss game), and so on.

The final item in the equation that really came to define today's amusement parks were rides. At first they might have taken the form of a boat excursion, simple swings, or a man/animal-operated carousel or ferris-type wheel. However, they became more varied and more sophisticated over time as manufacturers tried to outdo one another and the public demanded greater thrills. The first such rides began appearing in recreational locations in the 1840s, although it's possible, indeed - likely, that portable versions were at Canadian exhibitions and fairs before this.

|

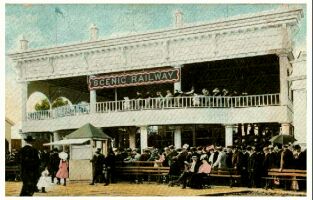

Dominion Park

Scenic Railway

Entrance circa 1905

|

Roller coasters, now a staple of any sizeable park, made their appearance in Canada in the mid 1880s, with the first ones at Hanlan's Point, Dundurn Park, the exhibition grounds in London, Brighton Beach, and in Septemeber at The Toronto Industrial Exhibition (later to be renamed The Canadian National Exhibition). The Dundurn Park one was probably the first continuous-circuit coaster in Canada.

When designers became more numerous and prolific, other parks began to add these rides, some even having more than one. As the coasters became more thrilling with higher hills, longer drops, tighter turns, and higher speeds, they turned into THE major drawing ticket at any park which had one, as is still the case today.

Coasters in Canada's past are well documented

in the accompanying Closed Canadian Parks

series of articles. (See at end.)

LODGING FACILITY

|

Hotel or cottage proprietors often became park owners because the amusements and attractions areas they had installed as additional draws became larger and more appealing to the public than the accommodations. Crow's Beach, Privat's (possibly Canada's first amusement park, dating from the 1840s) and especially Hanlan's Point, got their start this way. As patrons came to these places more and more for the diversions, the owners added additional rides and games. Some of those games eventually evolved into personal try-your-luck types or shooting galleries rather than just spectator-oriented competitions. Gradually these areas became known better for their amusements than for the accommodations or their natural offerings.

Many owners saw the opposite side of this and built hotels near already-established amusement areas as the rides and/or attractions drew ever larger crowds, many of whom wished to stay in an area more than one day. The Mansion House Inn on McNab's Island and the hotels at Crystal Beach are examples of this.

As these parks blossomed, exhibition promoters realised the potential draw of such areas. Although amusements and primitive rides can be traced back hundreds of years as additions to fairs, entire AREAS of games and rides began to be added to these exhibitions as an extra drawing ticket, particularly at industrial trade shows or country fairs. With the latter, farmers and small town residents were already used to seeing livestock, produce, baked goods and handicrafts, so the amusements were something additional to pique their interests. Many of these amusement sections became the main drawing ticket - sometimes even after the exhibitions themselves ceased to exist.

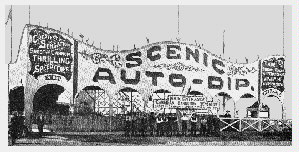

Canadian National Exhibition Scenic Auto-Dip 1902 - 1906 |

These amusement sections would eventually be referred to as "midways" in the years after the 1893 "World's Columbian Exposition" world's fair in Chicago, U.S.A. There, the amusement area was in a location called The Midway Plaiasance. The midway popularity at world's and other fairs led yet more to open parks expressly for that purpose, as is the case with most new amusement parks today. The name "Midway" became used by other amusement operators, both travelling and permanent, in emulation of the great fair.

|

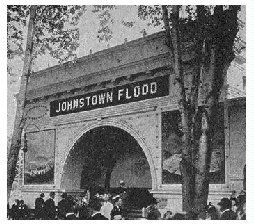

Dominion Park Johnstown Flood Exhibit circa 1908

|

Promoters also realised the value in spectacle, and so sideshows became part of the amusement equation. These included the familiar bearded ladies, "wild" men, birth defects, and other human oddities. Some fairs and parks opened "Infant Incubators" where babies were reared in glass cases. One of the most popular spectacle shows was the disaster display. There, people could see models or re-enactments of famous events such as the Canadian Victory at Vimy Ridge in World War I, or see disaster recreations such as Mount Vesuvius erupting at Pompeii, The San Francisco Earthquake and Johnstown Flood. Dominion Park and Scarboro Beach Park were two such parks that featured the latter type.

Examples of modern Canadian amusement parks that are, or were, closely tied to exhibitions are Happyland and Playland in Vancouver, Borden Park in Edmonton, and Expo 67's legacy: La Ronde, in Montreal.

TRANSPORTATION

|

Trolley and ferry companies also got into the act. Worker off-days generated little business for public transportation. The latter saw the potential of amusement areas to generate income, provided they were located at the end of one of their lines, or in the case of ferry companies, on an island, peninsula, or other location most easily reached over water via one of their boats. They reasoned correctly that if Canadians had some place to go during their time off, they might use a trolley, railroad, or ferry to get there & home again. (This was of course, before the large scale ownership of automobiles by individuals.)

Eventually, because the majority of Canada had Sunday as its off-day, the demand for amusement areas to be open then exceeded the power of religious groups to keep them closed. Thus, the transportation companies, which already had some business to picnic grounds on Sundays, garnered even more from those travelling to amusement parks on that day. By the mid to late 1950s or so, few parks were hindered from being open on Sundays, although many groups were powerful enough to prevent the sale of alcohol on that day until the 1970s. As well, when the five-day work week became standard, Saturday became a most popular day at the park.

For the trolley and rail companies, weekend business became even more important once they switched to electricity from horse or other power. The electric companies usually charged a flat monthly fee regardless of how much power was used. If the trolley and rail companies were able to create business on the weekends, they could generate additional revenue while paying no extra for the electricity consumed. Thus, profits would increase.

|

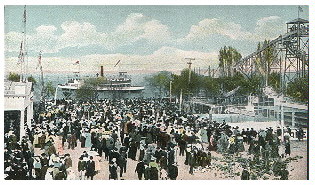

Hanlan's Point Boat Dock and Dry Slide, circa 1908

|

Many such companies first ran their services to already suitably located beaches or pleasure gardens, but later would buy into or completely purchase these places so they might exercise better control and reap additional profits. When this idea worked, these companies actually began to build or develop parks themselves. In some cases, the area was already a right-of-way for the rail company and it simply leased the empty land on either side of the tracks to concessionaires with the idea of starting an amusement district.

| Parks built or nurtured by transportation companies include: | |

|

|

The first three were essentially ferry parks... |

OTHER RIDES Shoot-the-Chutes at Scarboro Park Circa 1907 |

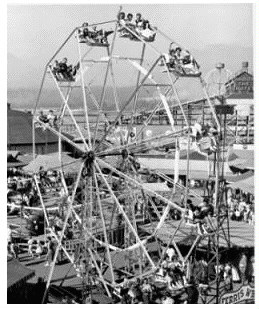

With the popularity of the amusement areas at these pleasure parks and beaches, came more rides. The ferris-type wheel and carousel had already been around for several centuries, but added to that and the already-existing roller coaster were new thrills. By the first two decades of 20th century, rides like the "Circle Swing", "Shoot-the-Chutes", and "Whip" were introduced, along with larger versions of the ferris wheel and roller coaster.

Whip and Ferris Wheel at Dominion Park circa 1920 |

With that reduction for many of the six-day work week to five days, increasingly available extra leisure time meant that amusement parks were becoming big business from persons eager for entertainment during those off times. Ride manufacturing enterprises proliferated, bringing even more amusement devices to the marketplace. Each company strived to better the others in the conception of new and varied rides. In the 1920s, these included The "Caterpillar", "Swooper", "Tilt-a-Whirl" and "Tumble Bug", among many others. With such new attractions becoming available on a regular basis, bragging rights for the latest thrill grew fierce, especially among amusement parks that had overlapping customer bases.

Although some of the early parks withered from competition, the trends discussed above continued up to and after the turn of the 19th/20th century. Many parks expanded or new ones opened throughout that time and into the 1920s. However, by that decade, the average Canadian was better able to afford an automobile and this meant those parks requiring access exclusively, or mostly by rail or boat, found business falling off, while those easily accessed by car saw sustained or increased patronage.

Nevertheless, even those parks had a tough time during the Depression of the 1930s, with many being sold off, falling into disuse, or reverting to nature parks and gardens. Some private ones were surrendered to local governments when their lease or other agreements lapsed and were not renewed by their cash-strapped lessees. (Compared to most other countries where the park owners are private or corporate, a disproportional number of Canadian parks were, and are, government owned.)

Today, many former Canadian amusement parks still have their names living on as nature parks, though the rides and attractions are long gone. Examples of past parks that were government owned for at least some portion of their existence are:

Borden Park,

Bowness Park,

Pither's Point Park,

Salter's Grove, and

Sunnyside Beach Park.

Those that did manage to survive into the days of World War II found their parks had deteriorated from lack of maintenance. Even though some business was to be had through entertaining Canadian and foreign military service personnel, some found it was not enough to cover the repair costs. Also, materials became harder to come by due to war shortages, so despite an increase in gate numbers, many closed in the 1940s.

|

Happyland Park in Vancouver Late 1940s, or 1950s

|

During these two hard decades some businesses became, or sold out to, carnivals. These outfits survived by going into areas that couldn't support a summer-long midway but could spend enough money in a one or two week period to make it worthwhile to be there. They would then move on to the next area for a couple of weeks, and so on. Nova Scotia's Bill Lynch got his start that way when he removed the amusements from Findlay's Pleasure Grounds on McNab's Island and went on the road in the 1920s. Casey Shows, Conklin Shows, and E.G.&J. Knapp are other Canadian carnival companies that owned parks and/or ran ride and arcade concessions in amusement parks in Canada. They would run road operations and rotate their rides and attractions among the parks and travelling shows. This led to a greater variety of rides for the customers and kept these companies solvent in areas where a park or travelling show alone would not have. Some would sell popular concession rides to a park and so profit from both the initial concession proceeds, plus make money on the sale.

Interestingly, in the 1940s and 50s when the permanent outdoor amusement business began to grow again in many areas, some carnival operators brought that trend full circle by buying, starting, or becoming allied with permanent parks and exhibitions. They would often supply midways for such ventures. Patty Conklin is best known for this as he acquired the Canadian National Exhibition midway contract almost 75 years ago and his descendants still run it today. Conklin also was part owner of Montreal's Belmont Park and often premiered new rides there. In Vancouver, West Coast Amusements bolstered the Happyland midway during the exhibition running. Some other examples of carnival-allied parks were Nova Scotia's Greenhill Lookoff and Rendezvous Park in Winnipeg.

Today, Canadian amusement parks are going

strongly with millions attending each season. Most large

centers have some sort of park within an hour's drive.

Here is a current

list of modern Canadian parks to peruse.

|

Although a good number of today's Canadian parks are large government or corporate ventures, it's not impossible to find parks that still exhibit some of the roots discussed in this essay. |

|

|

For those interested in rides history, many of the profiles contained in Closed Canadian Parks list rides and attractions - including manufacturers' names, where known. |

Richard Bonner

THE PRECEDING MAY NOT BE REPRODUCED

WITHOUT PERMISSION FROM THE AUTHOR ©

Return to

Canada's Outdoor Amusement Past

Return to the

Closed Canadian Parks

Introduction Page.