No Sweat

By Murray MacAdam

Many people who make the shirts on our backs don't make enough to put food on their tables. So some customers are starting to look behind the labels. |

The hip young models stare out seductively from the magazine ads, clad in the latest fashions from Gap or Club Monaco.

But behind the glossy photos, forgotten by most of us, are the people who actually make the clothes we wear.

People like Ana in El Salvador, who works in a maquiladora garment factory in a free trade zone outside capital city San Salvador. (Maquiladora is a common term for an export-oriented factory located in the Third World). Thirteen hours a day, six days a week - sometimes seven - she sews sleeves onto shirts. Ana doesn't like the long hours and weekend work, but her pay is so low that she and her children couldn't survive without the overtime.

The factory is hot and the ventilation is poor. Many of the women suffer respiratory problems from the fabric dust. They can only go to the washroom twice a day.

It's not a pretty picture. And yet for hundreds of thousands of workers, this is the reality of 'globalization,' as multinational corporations search for ways to make their clothes at a lower cost. Shareholders want profits, and consumers want bargains.

Impoverished countries, desperate for foreign cash and economic activity of any kind, compete for these factory jobs, offering bargain-basement wages and inexpensive (i.e. weak) health and safety standards.

If workers dare to organize unions, companies threaten to close down and move to greener pastures - green as in the colour of money. It's no idle threat. Hundreds of young women at one Guatemalan factory worked around the clock making Van Heusen dress shirts. They got tired of the 60-hour workweeks and poor wages, and tried to organize a union.

Ten years later, they won - or thought they had. Van Heusen simply closed down and moved the work to nearby sweatshops that pay even lower wages.

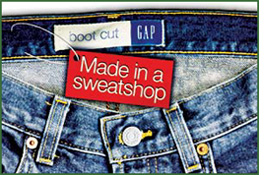

'Sweatshop' may be a word that brings to mind near-slave labour conditions from a century ago. But if you check out popular stores such as The Bay, Roots, Club Monaco, Gap or Eddie Bauer, chances are you'll find clothes made in developing countries that enticed corporations to their shores with promises of cheap labour.

Fortunately for Ana and the others like her, consumer awareness - and sometimes even outrage - has grown as more and more people learn of the miserable conditions endured by the workers who make our clothes.

Some shoppers are looking beyond their wallets and are asking questions about where and how their clothes are made.

"As business goes global, so is the movement against sweatshops," notes the Toronto-based Maquila Solidarity Network (MSN), which serves as a major focal point for Canada's growing anti-sweatshop movement.

MSN promotes solidarity with groups in Mexico, Central America and Asia organizing in maquiladora factories and export processing zones to improve conditions and wages. Targeting specific companies like Disney and Nike, and public education are all part of its work.

The Network is also lobbying the Canadian government to force companies to disclose where their clothes are made, using provisions under the Textile Labeling Act. The Act monitors what info should be put on labels of clothing. Currently, it only asks for washing instructions and fabric content, but sweatshop activists want the regulations revised so that consumers would know exactly where a piece of clothing is made.

This would not tell shoppers at a glance if the article was made in a sweatshop, but it would allow both activist groups and companies to better monitor their suppliers. The Conference Board of Canada is currently studying the impact of such a change.

So far, though, most companies have been reluctant to reveal what's behind the label, and the federal government has not yet used its powers to force mandatory disclosure. But some companies, such as Roots, have publicly supported the concept.

The MSN won a 2002 International Cooperation Award for promoting corporate responsibility from the Canadian Council for International Cooperation.

Not surprisingly, labour is a major player in the anti-sweatshop movement. The Toronto-based Union of Needletrades, Industrial and Textile Employees (UNITE) fights against sweatshops by promoting corporate responsibility and consumer action against exploitative companies. On the national labour scene, the Canadian Labour Congress is promoting "No Sweat" clauses in collective agreements.

Church goers are also helping to build the movement through Ten Days for Global Justice, a network of 180 local groups across Canada, now part of the Kairos justice coalition. As part of a campaign to close the rich-poor gap, Ten Days groups raised awareness about sweatshops by organizing "Wear Fair" fashion shows and by launching petition drives against sweatshops.

Activists do not want the sweatshops closed down. Factory closures that throw employees out of work only increase suffering and hardship among working people and their communities.

Nor do factory closures do anything to alleviate the abuse of workers. If companies are allowed to 'cut and run' from sweatshops targeted by activists, the same exploitation will surface in new factories opened elsewhere.

Instead, students, trade unionists, churches and others appalled at the suffering of sweatshop workers are joining forces to force companies to change. Fair Trade is the rallying cry. An Ethical Trading Action Group brings together Canadian Autoworkers, the Steelworkers Humanity Fund, Kairos, Oxfam Canada, Students Against Sweatshops and other groups to push for corporate codes of conduct among apparel companies.

A code of conduct includes promises that a company and its contractors will treat workers fairly by agreeing to:

- Pay a living wage that meets basic needs

- Stop forced overtime

- Ensure that workers have the right to form trade unions without harassment, threats or firings, and that they can engage in collective bargaining

- Commit to not using child labour or prison labour

In the States, groups such as the Workers Rights Consortium are also pushing to ensure that Codes of Conduct are enforced and workers' rights respected. Europe's "Clean Clothes" Campaign targets major retailers and major brands in ten European countries to promote decent wages and labour conditions for garment workers.

But a code doesn't mean much without commitment - and inspection. The issue of independent monitoring of workers' rights is crucial. A report on Wal-Mart sweatshops in Honduras found that no workers had ever heard of Wal-Mart's code of conduct.

"Going into these factories is like entering prison," says a Honduran priest. Teenagers and young women, often only 14 or 15 years old, put in 10 to 12 hours of grueling labour each day. After a few years many are so exhausted that they can't work anymore.

These realities continue to fuel consumer action. When Nike moved into Toronto's Kensington Market neighbourhood this past summer to launch its "Presto" sneakers, they weren't expecting to see a pair of sneakers dripping with red paint hung from a Presto sign. That 'greeting' was offered by local youth who, together with the Maquila Solidarity Network and UNITE, organized an anti-Nike street party to protest the company's labour practices. "Nike go home!" chanted the dancing youth.

By August Nike had had enough and pulled out of the Market. It was a very public defeat for a gigantic company that doesn't even have to mention its name because its trademark 'swoosh' is so recognizable around the world.

Nike has been targeted because of the treatment of the 500,000 workers, mostly women, who make Nike footwear (through local contractors) in China, Indonesia and Vietnam. The Nike Campaign has become an international movement demanding the company accept independent monitoring of working conditions at its contractors' factories, and that workers be paid a living wage.

Anger towards the company grew after news that on March 8, 1997 (ironically, International Women's Day), 56 women employed by a Nike contractor in Vietnam were forced to run around the factory in the hot sun until a dozen of them collapsed. They were being punished for not wearing regulation shoes to work.

Last April, 10,000 Indonesian workers took to the streets during a dispute about the minimum wage of $2.46 (US) a day. Nike spokesperson Jim Small responded by saying "Indonesia could be reaching a point where it is pricing itself out of the market."

Wages for Nike and Adidas workers in Indonesia are so paltry that some women workers are forced to send their children to live with relatives, according to a recent report. Full-time wages are as low as $2 U.S. a day.

But solidarity efforts can have an impact, even on a huge company like Nike. (For their part, Nike says that conditions are improving.) In September 2001, workers at Mexico's Mexmode factory, which makes sweatshirts for Nike, had their independent union recognized. It was a major breakthrough - the only independent union with a signed collective agreement in Mexico's 3,500-plus maquiladoras. Workers won pay increases and improved working conditions, after Nike was bombarded with thousands of letters from anti-sweatshop activists.

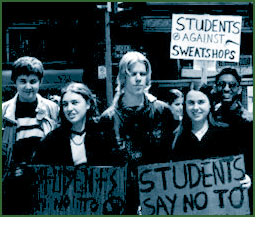

And many of those activists are students. Visitors strolling about the venerable stone buildings of the University of Toronto campus two years ago would have noticed something distinctly unusual: a banner hanging from a building demanding NO SWEATSHOPS. Inside, a group of students had occupied the office of then-university president Robert Pritchard to demand that the university approve a code of conduct guaranteeing that workers producing university merchandise received a living wage and the right to organize.

Ten days later, after Pritchard was flooded with emails and faxes supporting the students' demand, the university agreed.

The action was an early example of what has become a growing movement on Canadian campuses to ensure that university-identified clothes sold for students meet basic standards. U of T is just one of a number of campuses where students have banded together through Students Against Sweatshops to push for action. Students at 15 universities from one end of the country to another - Memorial in Newfoundland to Simon Fraser in B.C. - are campaigning for sweat-free campuses.

Their efforts are paying off. McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, recently became the eighth Canadian university to adopt a No Sweat policy to ensure its university apparel is not made under sweatshop conditions.

Nor are university students the only young Canadians galvanized into action. High school students and teachers across Canada are increasingly on board, promoting the adoption of No Sweat purchasing policies by their schools and school boards. Last August, as parents and students stood in line outside the R.J. McCarthy uniform store in Toronto, high school students handed them leaflets about sweatshops and how they could help ensure their school uniforms are made under human working conditions.

South of the border, a student anti-sweatshop movement has been woven together as well, with students at over 200 American campuses combating sweatshops under the banner of United Students Against Sweatshops. The New York Times called the student anti-sweatshop movement "the biggest surge in campus activism in nearly two decades."

Kevin Thomas, an organizer for the Maquila Solidarity Network, says that students have plugged into the sweatshops campaign because of the direct connection to the clothes on their backs. They've also realized that pushing companies and university administrations to adopt sweat-free policies can actually make a difference.

"Here's an issue where there's something you can do," says Thomas. "There's been real wins. Students respond incredibly well because they can see that their actions have an effect on the industry."

"Here's an issue where there's something you can do," says Thomas. "There's been real wins. Students respond incredibly well because they can see that their actions have an effect on the industry."

"I'm involved because of my interest in making links between my life and the lives of people around the world," says Jennifer deGroot of Winnipeg, a sparkplug in Manitoba's anti-sweatshop movement. It's pushing the provincial government to adopt a No Sweat purchasing policy. "I can use the power I have as a northern consumer to demand fair treatment of workers around the world."

Perhaps it's the influence of youth, but the grim reality of sweatshops hasn't drained this fair trade movement of creativity and fun.

Few social justice campaigns have used such a wide array of tactics - petitions, government and corporate lobbying, demonstrations, sit-ins, even "fashion shows."

And as Christmas fast approaches, harried shoppers at malls across Canada will again be stopped in their tracks as they hear:

Door bell rings, are you listening?

On your brow, sweat is glistening

You're working tonight; it just isn't right,

Slaving in a Sweatshop Wonderland.

and:

Shirts from Honduras

and Nikes from China

clothes made in sweatshops

in North Carolina

all wrapped in packages

and tied up with string,

these are a few of my

least favourite things.

What, then, does the responsible shopper do? After all, we need clothes, and no one is suggesting drab, Soviet-style utilitarian clothing. The idea is simply to use your purchasing power to help others make a decent living. Info on responsible shopping is available from groups like Shop for Change and Global Exchange, which publishes the Responsible Shopping Guide.

Unfortunately, it's not yet possible yet to know whether that stylish shirt you've been eyeing in the local mall was made in a sweatshop or not. That could change if the disclosure campaign is successful. Meanwhile, caveat emptor - buyer beware.

And buyer, take action. The harsh truth is than most consumers go for the bargains; it's understandable that we try to make our hard earned dollars go further. Yet the lowest price isn't always the best one - not if it involves sweatshop labour. The movement against sweatshops has blossomed because more people now believe we need to think about more than just prices when we shop.

Each of us, in how we choose to spend our dollars, can help reduce the demand for products made in sweatshops.

And that will give companies known to follow ethically based purchasing policies, such as Roots and the Mountain Equipment Co-op, the competitive edge.

Murray MacAdam is a Toronto-based writer specializing in community development and global issues.

Written December 2002.

| Return to Top

|

| Articles Archive

| About Our Times |