Small Change, Big Dreams

By Murray MacAdam

For the world's poor, getting a business loan can be next to impossible - they simply don't have the collateral the banks demand. But a growing 'micro-credit' movement is giving them a hand-up, not a hand-out, and the chance to make it on their own.

In 1976, Bangladeshi economist Muhammad Yunnus lent a group of 42 artisans 62 cents each, so they could buy the supplies they needed to eke out a living.

At the time, he didn't know he was starting a movement.

"When we started giving out tiny loans, we never imagined that one day we would be reaching hundreds of thousands, let alone two million, borrowers," says Yunnus, two-and-a-half decades later.

At less than a dollar each, they were 'tiny loans' indeed. But they helped, allowing the artisans to expand, however modestly, their businesses and improve their lives. And the loans were paid back. From that humble start has grown something called the Grameen Bank, the world's best-known micro-credit enterprise.

In a nutshell, micro-credit is the provision of small loans to people too poor to qualify for traditional bank loans. Small groups get together and act as each other's 'collateral' - if one fails, the collective carries the loss. It's a deceptively simple but powerful idea: without access to capital, it's difficult to start or grow a business, even tiny 'mom & pop' operations.

But for millions of people worldwide, that is reality.

The inability to borrow prevents poor people from getting the money they need to improve their lives.

Less that 2 percent of poor people have access to credit from reliable sources - moneylenders who demand exorbitant interest don't count.

Informal and small-scale lending arrangements have long existed in many parts of the world, especially in rural areas. However, in the past two decades, considerable more attention - and resources - have been shifted toward micro-credit lending. It is seen as a way to encourage self-reliance, create employment and, particularly, help women better their lives by generating some income.

Micro-credit (also called peer lending) is increasingly seen as an effective tool in the struggle against poverty, enabling those without access to lending institutions to borrow at normal bank rates and start small businesses.

Micro-credit schemes vary, but they usually share several key features:

- they're geared to people with no land or assets; that is, people who don't have what the banks call collateral;

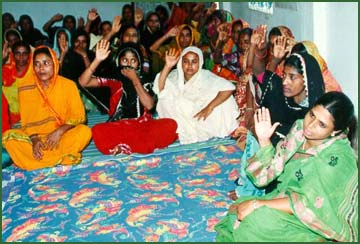

- borrowers become part of a small group of people who meet regularly to support each other;

- the majority of those taking part are women, because they are usually the poorest of the poor, with little hope of getting loans;

- borrowers can receive further loans, as long as earlier ones are paid, on the understanding that the poor need to have access to credit for a number of years to accumulate enough assets and savings to escape poverty.

- borrowers are free to choose the activity to be funded with their loan, with most loans going toward small businesses such as farming, handicrafts and shopkeeping.

It is estimated that 13 million poor people around the world are being helped by loans from more than 7,000 micro-finance institutions, with over $7 billion (all figures U.S.) in total loans. And the loan repayment rate is impressive, at 97 percent. Due to this success, micro-credit has been gathering momentum worldwide, growing 30 percent annually.

Many different players are behind this attractively simple development tool: non-government organizations (NGOs), donor agencies, international financial institutions and development advocates. Governments are also embracing micro-credit as a key economic development strategy among low-income people. The United Nations even has a special unit for micro-finance.

The Canadian International Development Agency, (CIDA, the foreign aid branch of the federal government), has long supported micro-credit. Each year it devotes more than $100 million toward micro-finance and micro-enterprise development in developing nations. CIDA is also part of an international consortium of 29 bilateral and multilateral donor agencies that support micro-finance, called the Consultative Group to Assist the Poorest. It works to improve the services and strength of the micro-finance "industry."

Bangladesh's Grameen Bank is by far the biggest micro-finance institution, widely admired as micro-credit's shining success story.

As with many small schemes, women benefit most, making up 95 percent of Grameen's 2.4 million borrowers. It is built on person-to-person solidarity, through the voluntary formation of groups of five people to provide mutual group guarantees, instead of the individual collateral required by conventional banks.

The small-group structure creates an atmosphere in which debtors know and care about each other, and ensure that they all meet their obligations. If one person fails, the group has to pick up the slack. It's a system that works.

The Grameen Bank remains the best-known case study of micro-credit, but there are many other projects out there. Some, like Grameen, are fairly large: Profund, for example, is a for-profit investment fund that helps over 300,000 small entrepreneurs in Latin America. A similar fund is getting underway in Africa, the AfriCap Micro-finance Fund, with $15-million in start-up funding. The money is coming from a number of international financial institutions including Canada's Calmeadow, which will manage the fund.

(While many Canadian NGOs have promoted micro-credit in the Third World, Calmeadow is unique in that it has helped fund and operate micro-credit initiatives in Canada as well as in Latin America and Asia. In the 'developed nation' of Canada, the focus is on Aboriginal and low-income people. Canada's largest credit union, Vancouver City Savings Credit Union (VanCity), also has a Peer Lending Program for people who normally could not get business loans. It operates much like the loan circle model made famous by Grameen. Four or more business owners who need loans join forces to support each other. In addition, VanCity offers International Community Investment Deposits that enable its members to invest in community loans funds that benefit low-income communities abroad.)

A typical micro-credit loan of $100 or $200 may not seem like much. But in a developing nation, a sum that small can transform a low-income person's life.

Blanca Rosa Cruz, a Nicaraguan mother of two, got a $200 loan from Opportunity International Canada, to start a pizza business. She became part of a neighbourhood loan circle of 19 women and one man. Cruz started making pizzas in her one-room, dirt floor home. Now, two years later, she employs six people, has fixed up her home and even has a savings account.

"I couldn't believe anyone would give me a loan without any collateral," says Cruz. "I am thankful to God that they trusted in me and gave me a loan."

She's one of over 260,000 people helped worldwide by Opportunity International, a Christian-based non-profit organization working to combat global poverty through micro-enterprise development. With average loans of $298 and a repayment record of 98 percent, women are helped the most (85 percent of borrowers), because they tend to be the poorest.

This is all well and good. But what is the real impact of the Grameen Bank and similar micro-credit programs? Do they make a difference in lessening the poverty that keeps over a billion people around the world struggling to survive on less than a dollar a day?

Grameen's Muhammad Yunus has no doubts. He believes that if financial resources are provided to poor people on reasonable terms, "...these millions of small people with their millions of small pursuits can add up to create the biggest development wonder."

Indeed, the facts bear him out - to a degree. The average household income of Grameen Bank members is about 25 percent higher than for non-members in villages with Grameen branches. Only 20 percent of Grameen members live below the poverty line, compared with 56 percent for comparable non-Grameen members.

"If we can come up with a system that allows everybody access to credit while ensuring excellent repayment, I can guarantee that poverty will not last long," claims Yunus.

Yet uplifting the world's poor to where their basic needs are met is not that simple. Lack of credit is by no means the only cause of Third World poverty.

Poverty arises from a range of causes, including poor prices for the crops grown by farmers, illiteracy, crippling debt burdens, poor wages, lack of land, poor training and much more.

As a UN report on micro-credit's role in eradicating poverty says, "In some of the lowest-income countries, lack of access to land is the most critical single cause of rural poverty...Yet few countries have substantial land reform programs."

Specific anti-poverty strategies have to be considered and developed in the social, political and economic contexts of the communities and countries involved. Oxfam notes that "Poverty alleviation is rarely an issue of simply improving access to financial resources. Poverty is more than a lack of material resources - it also concerns the denial of basic rights, control, access and power."

Even the World Bank has admitted that micro-credit alone is no cure-all for poverty reduction. Only people with the ability to run a business can borrow, leaving out those people without the necessary skills and training. So other development efforts such as literacy promotion, training and job creation are needed to complement micro-credit projects.

And although the ability of micro-credit to uplift women has been widely praised, a debate is now simmering over the impact of peer lending on the lives of women. The United Nations holds the view that micro-credit has been positive. "We have learned that when women gain economic autonomy, the health, nutrition and education of other members of the household, especially children, improve at the same time," says Noeleen Heyzer, executive director of the UN Development Fund for Women.

Alemnesh Geressu, a member of the Women's Poverty Lending Program of Catholic Relief Services (CRS) Ethiopia, serves as an example of that improvement. She lives with her husband, a poor farmer with no land, and their six children. For years she survived by doing a bit of trading. But local moneylenders skimmed off much of her earnings, charging her 10 percent interest or more per month on loans.

That bare-bones existence changed after receiving her first loan from CRS in 1995. She expanded her business of selling grain in the local market, and is also growing vegetables and ploughing a plot of land in co-operation with other members of her solidarity group.

Geressu sees a real improvement in her living conditions - and in her attitude. She now has enough money to buy things for her family and is sending two of her children to school. "I have more confidence in myself and I wish the program could accommodate more women to improve their lives."

Geressu's story illustrates the three main ways in which micro-credit can help poor women:

- by providing independent sources of income outside the home, it can reduce women's economic dependence on their husbands and thus increase their autonomy;

- those independent sources of income, together with the exposure to new ideas and social support can, in theory, make women more assertive of their rights;

- and by providing control over material resources, micro-credit programs can raise women's prestige and status in the eyes of their husbands, opening up new possibilities within families.

Many people are confident that micro-credit does indeed bring about these positive changes. Abdul Bayes, co-author of a micro-credit study in Bangladesh, concluded that "NGO credit programs in rural Bangladesh are not only likely to bring about rapid economic improvement in the situation of women but also hasten their empowerment. The NGO credit members are reported to be more confident, assertive, intelligent, self-reliant and conscious of their rights."

Yet others in the development field are not so sure. They worry that loans, by themselves, cannot uplift women from their difficult situations. Aminur Rahman, a Canadian doctoral student, uncovered some disturbing findings when he returned to his native Bangladesh to examine how the Grameen Bank has improved the lives of women.

Of the 120 female borrowers in his study, 70 percent admitted they endured increased verbal or physical violence from male relatives after taking out loans. And while the loans were supposed to help them earn income, more than 60 percent of the loans were actually used by men. "It was a shock," says Rahman. "The Bank has a really good objective, but there is a gulf between its philosophy and its field realities."

Part of the problem involves women's lack of access to formal education, says Peter Noteboom, a Canadian development consultant who has worked in community-based micro-credit programs in Bangladesh and Haiti.

It's not uncommon in Bangladeshi villages, adds Noteboom, for no women in a loan circle to have the skills needed to do the group's bookkeeping, since they have not been able to go to school. So a local man who has been able to acquire those bookkeeping skills is invited to take on that critical role. And he assumes the power that goes along with it.

Lack of credit is only one piece of the poverty puzzle. Loans need to be linked to capacity building and the skills individuals need to transform their lives.

Others agree that it's unrealistic to expect that micro-credit, by itself, can act as a panacea for poverty alleviation. "For example, we've got to be careful that we don't put everything we have in micro-credit programs and neglect the fact that children in developing countries need to be immunized as well," says CIDA president Huguette LaBelle.

"And you still need, for example, [improved] rural roads - otherwise the poor will increase their agricultural yield, but they won't be able to take it to market."

Grameen Bank boasts that it contributes more than 1 percent to the GDP of Bangladesh. Yet a quarter-century and several million loans later, Bangladesh remains one of the poorest, least-developed countries in the world. Three out of every five adults can't read or write, average life expectancy is only 59, and GNP per capita is just $350.

Clearly, its impoverished citizens need a lot more than micro-credit.

But the micro-credit movement is growing nonetheless, and will continue to grow in the foreseeable future. In November, 2002 the U.S.-based RESULTS Educational Fund, one of the world's leading micro-credit promoters, is sponsoring a huge "Micro-credit Summit +5" conference in New York.

It will review progress made since a 1997 gathering that launched a campaign to reach 100 million of the world's poorest families with credit for self-employment and other services by 2005. That event attracted over 2900 delegates from 137 countries.

This year's event promises to be even bigger, with more than 3,000 delegates from over 140 countries expected, including heads of state. It will assess progress toward the ambitious goals set in 1997, and identify strategies for reaching them. This major event will bring the gospel of micro-credit to even more people. And it will undoubtedly result in further resources being devoted to micro-financing.

There are certainly enough good news stories to support the concept of micro-credit, and support for the poorest of the poor is desperately needed. But only time will tell if the micro-lending is a band-aid solution for some, or a broader movement giving the world's impoverished the boost they need - and the chance they deserve - to make it on their own.

Murray MacAdam is a Toronto-based writer specialising in community development and global issues. Written April 2002

| Return to Top

|

| Articles Archive

| About Our Times |