Buddha was a Lumberjack

By Katharine Sandiford

A meditating eco-logger in Nova Scotia sees the forest for the trees

Jim Drescher is not your typical lumberjack. Sure, he cuts down trees, mills the logs and sells them. Yeah, he's got big strong hands, wears tough denims, checkered shirts and steel-toed boots. But unlike most loggers, Drescher spends a lot of his time in the woods meditating. He's a practitioner of what he calls "contemplative eco-forestry" - a custom blend of forest ecology and Buddhism, a way to cut down trees without cutting down the forest. In fact, the primary goal of his business is to keep the forest healthy and resilient.

"The forest is the final product," says Drescher. "The lumber is just a perk." Drescher's 'product' is Windhorse Farm, 150 acres of sustainably harvested old-growth forest on Nova Scotia's windswept South Shore.

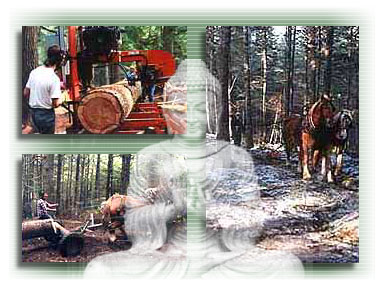

What keeps his forest healthy is his method for harvesting the trees. Drescher only selects a few hundred trees, never taking more biomass then can be replenished in a year. He only cuts in the winter when the ground is frozen and coated in snow, to prevent damage to the surrounding soil and plants.

He doesn't bring in heavy machinery, but rather a chainsaw and small portable mill. Instead of trucks and tractors, he uses his two giant Clydesdale horses to haul the logs over the frozen ground. The logs are milled in different spots throughout the forest, leaving all the sawdust, wood chips, branches and bark behind to decompose, to give nutrients back to the soil. The horses then carry out the planks to the meadows where they are stacked for drying.

A walk in his woods is to go to a place most think no longer exists in the Maritimes. Massive trunks surge out of the ground into the sky - up where arching green needled branches make a vaulted cathedral canopy. Bright green sponge moss carpets the forest floor. Pale green stringy lichen grows like unwanted hair off tree limbs. Ferns and saplings poke out of the moss carpet and catch whatever beams of light have filtered through the foliage overhead.

The air is fresh - the real fresh - a blended scent of pine, hemlock, fern and earth that manufacturers of air fresheners aspire but fail to reproduce.

"All of Nova Scotia once looked something like this," Drescher says. "But there's only five percent of forest left in the province that displays the characteristics of the natural Acadian forest." Practices such as clearcutting have stripped Nova Scotia of much of its natural wealth.

Drescher is a logger, and also a dedicated member of the Shambhala Buddhism community. Tibetan monk Chogyam Trungpa Rimpoche started this Westernized form of Buddhism in the late sixties, based in the hippy-mecca of Boulder, Colorado. In the late seventies, with almost a thousand followers, he moved his headquarters to Nova Scotia. Over the eighties, hundreds of families relocated to Halifax to be with their Shambhala community. Jim and Margaret Drescher were among Rimpoche's closest students and were chosen to be among the first six to make the move in 1979.

Born on a farm in Wisconsin in 1942, Drescher enjoyed an early education in forestry and ecology. His father William, a hydrologist by training, also managed a commercial woodlot on the family farm. His grandmother Margarite was an avid naturalist. She and young Jim used to go on long walks together - watching and learning. Although his family raised him as a Christian, he left that theology behind on the farm, but took with him a strong devotion to morals and ethics.

After he graduated in 1966 from the University of Wisconsin with a Masters degree in Ecology, he taught for a few years at the University of Washington. In 1973, he met Trungpa Rimpoche and moved to Boulder, Colorado so that he could pursue studies in Buddhism.

When they moved to Nova Scotia in 1979, Jim and Margaret set up home in Halifax. Although he consulted in the forestry business on the side, he worked in the coastal city for a successful construction and real estate company.

But he was happy to give all that up when, in 1990, he discovered a special piece of land for sale. It's a pretty rare thing in Nova Scotia, to find land with old growth forest. Even rarer is the family that sold it to Drescher. The Wentzells were the original owners and had kept it in the family for four generations while following the strict "eco-forestry" principles laid out by Conrad Wentzell, the original owner.

Carol Wentzell would have passed the land down to his son, only he and his wife were childless and aging. A year before Carol passed away, Drescher sealed the deal.

Drescher sets aside time in his day to wander aimlessly through the original Wentzell forest. Sometimes he crawls, sometimes he rolls around, sometimes he splays out on his back across the needles, and sometimes he just sits and meditates. But whatever he's doing, he's not thinking about the forest with his brain, he's feeling it with his heart.

Although he doesn't preach or encourage any of his employees to meditate, he does want everyone who works for him to develop a deep connection to the forest. Anywhere from five to 11 people work at Windhorse at any given time. There are usually around five full-timers, including a forest manager, a business manager, two carpenters in the woodshop and a full-time gardener. It changes season by season and often he has volunteers or interns working for room and board.

Windhorse makes the most of its trees in the woodworking shop by converting the logs into flooring, shingles and cabinets. Value-added is an important concept in sustainable forestry. Jim also runs the "Ecoforestry School of the Maritimes," and offers courses to youth, woodlot owners, forest managers and Buddhists. Margaret, who's in charge of the gardens, sells organic produce at farmers' markets.

Surprisingly, Drescher never uses naturally felled dead trees - too many animals and insects depend on them for habitat. "Dead wood is the life of the forest," he says. "It's one of our eco-forestry slogans."

Windhorse Farm operates under 31 of these slogans - bits of wisdom collected from around the world. A big one for Drescher is: "Sustainability through diversity." The more diverse an ecosystem is, the stronger it will be. When selecting what trees to cut, he never cuts the tallest trees, as he wants as much diversity in heights and ages as possible. An even-aged stand is structurally weak. The more species of animals, plants, insects and bacteria a wild area has, the stronger the forest will be. He never cuts underrepresented tree species.

"Slow the Water" is another key slogan. The more a creek meanders, the longer it keeps the water around for the plants and animals that need it. The more contours in the forest floor, the more opportunity there is for water to be collected and stored. Machines and roads are not allowed in his forest because they compact the earth, creating a hard surface for rain to quickly run off into the rivers. Down in the meadows and gardens, Jim and Margaret have turned a short 500-metre long creek into a meandering system of ponds and wetlands several kilometres long.

Drescher has had his Buddhist teachings put to the test while dealing with emotions of anger, sadness, and depression after an elderly neighbour sold off all her trees for a retirement fund. The resulting clearcut, smacked right up against his forest, is like a desert outside an oasis. Drescher eventually learned to accept the situation and even look on it positively.

"It will grow back. It might not be the same forest when it does, and it might take a thousands of years to achieve its former level of complexity, diversity, and overall magnificence, but it will grow back."

Drescher has learned to be patient and let the forest teach him what he needs to know. "We may not know how a forest works, but we can unearth some of its knowledge to help keep the forests we work with strong."

And he has had excellent human teachers too, he says. "There's Merv Wilkinson who's been doing all this out in B.C. for decades. My father. Trungpa Rimpoche, who is my guru, but who is unsurpassed as an ecology teacher."

And the Buddha, Jim Drescher might add, who didn't just sit under the bodhi tree - he also cut them down from time to time.

Written December 2003.

| Return to Top

|

| Articles Archive

| About Our Times |