Call of the Wild

by David Napier

A growing number of Canadians are realizing the eco benefits - economic, that is - of donating their land for conservation. |

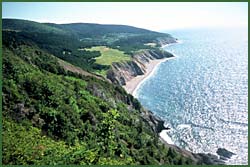

MacKinnon's Brook hugs the western edge of Cape Breton Island like a green blanket. This is a place where the trees touch the clouds, cliffs plummet to the ocean, and wildlife roams free over 2,000 lush acres.

It's easy to believe such stunning surroundings could never be harmed. But in a world of logging, mining and golfing, the degradation of a pristine piece of Nova Scotia is not out of the question.

Enter the Nova Scotia Nature Trust.

The Halifax-based conservation agency is one of a growing number of non-profit organizations in Canada that operate under a mandate to preserve and protect some of the country's unique and valuable green spaces.

In the case of MacKinnon's Brook, the Nature Trust is negotiating with Jean Rosner and a handful of her neighbours to have a conservation easement placed on the land. This legal agreement would permanently limit the use of all or part of MacKinnon's Brook, effectively protecting the native flora, fauna and trees that provide a natural habitat for dozens of black bears, deer, ospreys and bald eagles.

"Ecologically speaking it's not just the shoreline," says Bonnie Sutherland, Executive Director of the Nature Trust. "[The area to be protected] extends well back into the highlands."

MacKinnon's Brook is where Rosner, an 85-year-old grandmother from Concord, Massachusetts, has summered for more than 60 years. She has earmarked 1,000 acres for protection from development.

"In the late 1960s, an automobile salesman from Boston wanted to buy the land and put up a thousand tourist cabins in the meadow," says Rosner. "It was a tax sale, and he was offering $1 an acre. I offered $2 an acre and bought it," she adds with a chuckle.

This was thirty years before the Nature Trust existed, and long before Rosner ever heard of the Nature Conservancy of Canada.

A lot has changed since then.

Founded in 1962, the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) has contributed to the protection of more than 1.67 million acres of ecologically significant land across Canada. These lands stretch from Francis Point in British Columbia to Pelee Island in Ontario to Gaff Point in Nova Scotia - a combined area greater than the total acreage of Prince Edward Island.

In recent years, the NCC and other regional conservation groups such as the Nova Scotia Nature Trust, the Prince Edward Island Nature Trust and the Ontario Nature Trust Association have been enjoying a boom, of sorts.

The NCC's work for its last recorded fiscal year (1999-2000) resulted in the preservation of 122 properties across Canada, a hefty increase of 45 percent over the 84 properties preserved in the previous year. For its part, the Nova Scotia Nature Trust has enjoyed considerable success as well, having secured or identified more than 20 properties for protection.

Altruism is the main motivator for people to donate their land for protection purposes, but there is also, thanks to recent changes in Canada's tax laws, good economic sense behind giving away green spaces.

In 2000, Finance Minister Paul Martin made it much more attractive to donate land under the Ecological Gifts program. Created in 1995 after a decade of lobbying on the part of scientists, environmental organizations and provincial governments, the EcoGifts program gives tax credits to individuals based on the value of gifted lands.

When an ecological gift is made, the donor realizes a capital gain as a result of transferring the title on the land. In return for their largesse, those who donate land to the government or an organization whose primary purpose is land protection get a tax receipt for the value of the land. This tax credit is applied against as much as 100 percent of a person's income, and can be carried forward for up to five years.

Until last year, the green conscentia were forced to pay tax on most of the capital gain. But in 2000, the federal Liberals adjusted the Income Tax Act so that rather than pay tax on 50 percent of the capital gain, as is the general rule, only 25 percent of the capital from donated land is now taxable.

There is, however, considerable work yet to be done at the legislative level if ecologically significant land is to be saved from the bulldozers. "Putting any tax on a gift is a major problem," says Sutherland of the Nature Trust. "[Ottawa] should just say that there is no capital gain."

Until that happens, many potential donors are irked that their goodwill gets taxed. "Many people say, 'When the federal government gets rid of the tax, come back and talk to us'," Sutherland says.

Ian Attridge, an environmental lawyer based in Peterborough, Ont., feels that the EcoGifts program provides a "major incentive" for land-owners to turn over property, either as a straight donation or by allowing for a conservation easement to be placed on the land. But he agrees that legislation, particularly at provincial levels, can be cumbersome. "For example, if a property developer decides to donate land he doesn't qualify for a capital gains exemption," he says. "There are gaps in our incentive programs."

The urgency of the conservation situation comes as clear as a Cape Breton sky when one realizes Canada's place in the grand ecosystem. Canada is home to 144,000 of the world's species; 25 percent of the world's wetlands; 10 percent of its renewable freshwater resources; and 15 percent of the globe's forests. John Lounds, President of the NCC, has said that, "Over the next decade, if we are going to conserve priority lands, Canadians probably need to invest $2 billion."

Meantime, the trend toward donating land for protection continues, thanks in part to many companies that have heard the call of the wild.

The Canadian arm of Shell (perhaps not ironically a corporation criticized for environment and human rights abuses) donated 22,000 acres in southeastern British Columbia (value: $1.8 million) to the Nature Conservancy of Canada. Likewise, Suncor Energy played a pivotal role in helping the NCC acquire Middle Island on Lake Erie in 1999. TD Canada Trust runs its Friends of the Environment Foundation, and the Mountain Equipment Co-op has supported the NCC since 1987 through its Environment Fund.

Whether it's good business or goodwill, the act of saving areas such as MacKinnon's Brook seems to be catching on. Instead of hurling themselves in front of logging equipment in protest, those individuals who can afford to do so are turning over their land to nature groups in the form of donations or with conservation easements.

An ecologically revamped tax system would help. But even before Paul Martin's latest moves there were trailblazers like Jean Rosner.

She was so committed to the land protection cause that she spent money she had saved for her children's education on a massive slice of Cape Breton real estate.

"The money was supposed to go toward their college tuition, but it didn't," she says. Instead Rosner spent it on land that she eventually used for a camp for kids, which ran for 25 years (earning her the nickname "Hippie Queen" from local residents).

These days, Rosner's children - which she proudly points out all attended college - bring their kids to Nova Scotia every summer to give them a unique education. It's the kind of schooling that comes from being in the great, untouched outdoors.

"Some people believe in hanging on to their land. They don't want to give it away," says Rosner. "I believe in sharing what I have with others."

And the 'others' will now include many generations to come.

David Napier is a Halifax-based writer.

Written August, 2001

| Return to Top

|

| Articles Archive

| About Our Times |