Helping Haiti

by Paul Weinberg

How can the international community help Haiti, one of the poorest nations in the Western Hemisphere, recover from its latest natural disasters?

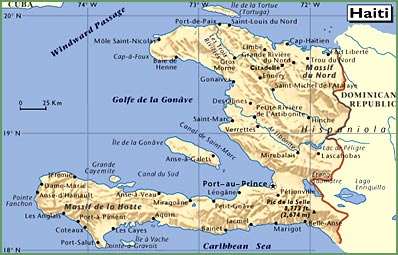

Cuvette is the word Ghislain Rivard uses to describe the scene in May after floodwaters coursed down mountains from all directions into a valley in southeast Haiti, drowning 1,600 inhabitants of Mapou. The French expression means 'no way out.'

"Overnight, the village disappeared under water," says the Montreal-born and Port Au Prince-based director of programs for Haiti at Save the Children Canada. "Now, there is a lake and the lake will be there for the next three years."

No way out is probably how the 200,000 left homeless, hungry and thirsty in northwest Haiti felt in the face of September's Tropical Storm Jeanne. At least 2,000 are confirmed dead, but hundreds more are missing.

Hardest hit was the town of Gonaïves, where a gnawing desperation accompanies the thirst and hunger. Their town was engulfed in mud and misery: homes have been swept away, roads washed out, and every one of its 100 schools has been destroyed.

Rivard's organization is one of many non-governmental organizations (NGOs) trying to provide emergency relief to rural communities in the wake of the floods and the storm. After the May disaster, Save the Children set up temporary facilities with plastic sheets for 4,500 surviving children from the outlying region around Mapou. Since 23 schools were destroyed, a summer camp for children aged 5 to 18 was quickly set up to make sure "the kids could have their final year exam in the primary school," says Rivard.

No way out is how many people in Haiti feel far too often, in a country that seems cursed with strife, repression and very bad luck. For aid officials working in Haiti, the most recent natural catastrophes represent just the latest chapters of a longer tale of distress and disaster.

Since trees are a source of fuel, income and survival for many rural poor - trees are chopped and burnt into charcoal - entire mountains have been stripped of forests. The resulting soil erosion makes valley communities vulnerable to mudslides and floods during heavy rains.

And in Haiti, almost everything imaginable is lacking: hospitals, doctors and nurses, schools, roads, electricity and basic security. Decades of dictatorship and political turmoil paved the way for thousands of skilled Haitians to escape a country that desperately needs them, for the safer and more prosperous shores of Canada, the U.S. and Europe.

Ghislain Rivard is a 20-year veteran of international aid projects that have taken him to countries including Burkina Faso and Indonesia. He expects to be in Port Au Prince for the next two years as part of international reconstruction efforts for Haiti. A top priority will be working with the Haitian ministry of education officials to build new and permanent schools. "CIDA [the Canadian International Development Agency] is interested in working with Save the Children for mid-term and long support."

Described as the poorest in the Americas, Haiti is a country that usually gets missed by journalists - until an armed coup or natural disaster puts in back on the media radar. But it has now joined countries like Bosnia and Cambodia as the target of an aid rescue effort that combines the provisions of basic needs and governance reform.

At a conference on Haiti held in July in Washington D.C., the major donors - the U.S., the European Union, the Inter-American Development Bank and the World Bank - pledged upwards of US$1.91-billion. Canada promised aid totaling Cdn$180-million.

Canada has always been cited as a natural supporter for Haiti's development because of a shared Francophone heritage and the presence of about 150,000 people of Haitian origin, primarily in Quebec. However, the Canadian government had decided last year to de-list Haiti as a priority country and aid to that country had been cut by half.

But tumultuous events this past February - when the democratically elected president Jean-Bertrand Aristide was forced into exile during an insurrection by former members of the previous military regime - put Haiti back on Canada's foreign policy map. An interim government supported by the U.S., the French and the United Nations has been installed in Port Au Prince.

The current government, which includes members of the Haitian Diaspora in North America, is headed by an appointed interim prime minister, Gerard Latortue, a former South Florida Haitian radio talk show host. He is expected to resign and stay out of politics when a new elected government comes to power in 2006. The international community appears willing to unleash development funds during this transition period.

"My understanding is that [the present Haitian government] is aware of what is at stake. They need to maximize their success. The international community is saying this is your chance to make sure things work out in Haiti," says Emmanuel Isch, a director of emergency relief at World Vision Canada.

But some experts on Haiti are questioning whether this reconstruction effort is simply a quick fix. Carlo Dade, a senior official at the Ottawa-based Canadian Foundation for the Americas (FOCAL) notes that United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan spoke originally of a ten-year commitment to Haiti, but that idea has since been dropped.

Also, Dade suggests that the triple series of elections planned for next year (local, legislative and presidential, which Canada will play a major role in setting up), are premature in a country where the priority should be the provision of basic needs such as garbage pickup, disease prevention, the building of roads and the repair of water systems.

With Aristide out of the picture, the squabbling opposition politicians in Haiti are not inspiring the population, says Dade. "This same cast of characters sit on the electoral ballot. I don't know how much support and enthusiasm they are going to generate in Haiti. They have not had a new crop of leaders come forward."

Washington-based commentator Larry Birns worries that enough money won't get to Haiti. He draws parallels with the U.S. failure to contribute towards the rebuilding of institutions in Afghanistan after the overthrow of the Taliban government. "The amount announced or pledged by donor conferences in reality often comes at half or even less of the pledged amount."

Caroline Anstey, country director for the Caribbean at the World Bank in Washington, denies reports that little of the promised aid money has been spent in Haiti. "Well, it is happening, but I would be much happier if it was happening more rapidly." She says that her organization has already spent funds for such "high impact" initiatives as the restoration of electricity and the clean up of garbage in Port Au Prince.

The World Bank is also working with other donor agencies to protect areas from further flooding. This includes reforestation, disaster management, early warning and the building of adequate roads to connected outlying communities. "It is essential to have some quick benefits for the Haitian people. It is also essential to make sure that some of the reforms that everybody wants to see are focused on anti-corruption, greater transparency, and a greater role for civil society."

But the bulk of the loans and grants will be made available for specific projects submitted by the Haitian government. Oxfam policy advisor John Ruthrauff says it could take a year before many get off the ground. A major issue is simply the weakness of the Haitian government ministries and the challenge in negotiating and monitoring contracts with the various national donor agencies from the North, each of which have separate requirements.

Ruthrauff presumes that some of the returning Haitian expatriates will end up taking charge of this responsibility. "Haiti is more difficult because the government has collapsed. And it has been a problem for a number of years. There is not a lot of expertise in the government at the moment."

Meanwhile, armed groups - pro and anti-Aristide - continue to be active in Haiti. Former members of the Haitian military (abolished during Aristide's tenure in power) have occupied some towns in the country and ignored the government's call for disarmament. But Birns and others have also criticized the administration under interim Prime Minister Latortue for focusing their policing on the arrests of Aristide supporters rather than fighting crime.

Michael Dash, a Trinidad-born professor of French and Africana studies and a keen observer of Haitian politics, doubts that free and fair elections can occur in the current climate. The New York University academic is particularly concerned that Guy Philippe, a high-profile armed rebel reportedly linked with drug trafficking might end up winning the presidency because of popular skepticism towards democracy following Aristide's rule, and the failure to live up to expectations.

But a Haitian university administrator who lived in Canada for 15 years, and who was a supporter of the civilian opposition that played a role in Aristide's overthrow, points out that although the Haitian military was an intimidating role force in 1990, the Caribbean country managed to stage free and fair elections. That campaign led to Aristide's coming to power for the first time.

What complicates the establishment of an independent electoral tribunal in 2004 is the refusal of the Fami Lavalas party (Aristide's political movement) to participate in the formation of the tribunal, says Herard Jadotte, general secretary of Notre Dame University in Port Au Prince. "Some of the [Lavalas] leaders are accused of corruption or serious human rights violations, and the judicial system mechanisms are not yet in place to give them fair trials."

A bigger issue for Jadotte is the lack of long-term planning in the current reconstruction for Haiti - "it takes time and it's expensive." He notes that while Bosnia has received aid totaling US$67.6-billion to date (the European Union is a major investor), other troubled states such as Mozambique, Cambodia and Haiti, are receiving an average of US$2.55-billion.

The university administrator adds that "there is very little analysis being done of the lessons learned in the 1994 to 2000 period [the last time the international community unleashed aid dollars for Haiti] of what was accomplished in justice and police, for example, and what went wrong, what can be learned."

It is impossible to discuss Haiti's development without mentioning Aristide's legacy. He was elected in 1990 as a major social reformer, but was overthrown just a few months later by the Haitian military. Four years later the U.S. military, courtesy of U.S. president Bill Clinton, brought him back to power.

During the period that his Fami Lavalas party ruled Haiti, the country "was forced" to adopt extreme market policies of the World Bank and other international donor agencies, which included privatization and the abolishment of subsidies for rice farmers, says Stephen Baranyi. Principle researcher in conflict prevention at the Ottawa-based North-South Institute, Baranyi says that such measures "aggravated some of the structural economic policies that Haiti was experiencing. Massive unemployment, for example."

Aid workers like Ghishlain Rivard try to stay away from these political questions, although they can get in the way. His priority is to help children in need wherever Save the Children Canada decides to send him. He finds Port Au Prince and Haiti at large safe if he avoids going out at night or on certain streets or communities. The UN releases a daily bulletin (much like a weather report) that indicates no-go areas because of the activity of particular gangs or political groups. Kidnappings happen, but this is not like Iraq. The primary victims are "rich Haitians, for now," he says.

Rivard cannot help being affected by the jadedness of veterans in international aid who mutter that the latest reconstruction effort is a repetition of previous failed efforts in this country. "Some people who have been here for years and years say 'well, we have seen that before.' Six years ago, ten years ago, it is always the same scenario."

But the Haitian people have proved their resiliency, and Rivard says the world cannot turn a blind eye to their plight. He still believes that for Haiti, with the strategic help of the international community, there is a way out.

Written October 2004.

| Return to Top

|

| Articles Archive

| About Our Times |