A New Deal for Africa?

By Murray MacAdam

Is the 'New Partnership for Africa's Development' a new Marshall Plan that can uplift Africa the way Western aid rebuilt post-war Europe? Or is it simply a way to lure Africa into corporate-dominated globalization?

The verdict is still out on what the hotly debated 'New Partnership for Africa's Development' (NEPAD) holds for Africa's people.

Launched October 2001, NEPAD is an ambitious plan for sharply accelerating development in Africa. It's based on an analysis of the problems facing the continent and a program of action to resolve them. NEPAD emerged from the Organization of African Unity, with South African President Thabo Mbeki playing a strong leadership role.

It will be the centrepiece of the "African Renaissance," claims Mbeki.

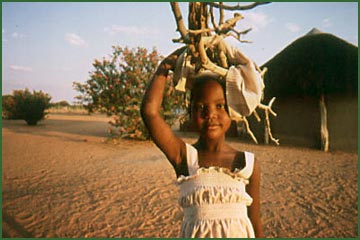

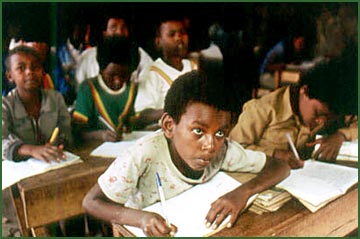

The plan is challenging because Africa's problems are staggering. Half of the continent's population - 340 million people - struggle to survive on less than $1 a day (all figures U.S.). A Canadian born today, on average, can look forward to 79 years of life. But for an African, that lifespan is only 54 years. Only 58 percent of Africans have access to safe water.

Then there's the AIDS pandemic. Of the 40 million people worldwide infected with HIV, more than two-thirds live in sub-Saharan Africa. In fact, the current average lifespan of an African is forecast to decline between now and 2015 because of both AIDS and growing poverty.

NEPAD represents an effort by African leaders to climb out this morass of poverty through sustainable growth and development. More specifically - and controversially - by accelerating Africa's integration into the global economy.

The plan also recognizes that for Africa's economic marginalization to end, more than just economic factors come into play. There must also be peace on a continent long plagued by war, and respect for human rights, democracy and good governance. This will help make Africa attractive for investors.

These, and many other challenges facing Africa, are discussed in the NEPAD document. It also includes specific targets, including an ambitious (some would say unrealistic) GDP growth of over 7 percent per annum for the next 15 years. If accomplished that could cut Africa's poverty rate in half by 2015, one of the millennium development goals agreed upon by the United Nations in 2000.

Since sub-Saharan Africa's current growth is only 3 percent, more than doubling it to 7 percent will be tough indeed. But not impossible. Countries like Uganda, Mozambique and Botswana are already achieving these impressive levels of growth.

Africans Leading Africa Out of Poverty

Its advocates see three key features for NEPAD that set it apart, in positive ways, from other development plans.

First, it is African developed and managed - by Africans for Africans. NEPAD recognizes that Africans must be the architects of their own future, and Africa must gain freedom from control by foreign superpowers. Second, it includes the concept of a new, more equitable partnership between African nations and development partners. And lastly, Africa is itself taking on certain commitments as part of the plan, which are not imposed on it from outside.

Indeed, there are hopeful signs that NEPAD can represent a paradigm shift in Africa's relationships with international development agencies. That shift can be summed up in a simple but key phrase spoken by K.Y. Amoako, executive secretary of the Economic Commission for Africa: "Africans must lead Africa out of poverty."

This new model, says Amoako, includes African leadership and ownership of its development policies and programs, requiring good governance, a capable state, sound economic management and the participation of all sectors of society.

NEPAD is "a strong beacon of hope for Africa," says Dr. Genevesi Ogiogio of the African Capacity Building Foundation. "It is a critical intervention if Africa is to succeed in effectively reducing poverty and achieving sustainable growth in the first two decades of the new millennium."

For a long time, western countries have been telling African countries how to solve their economic and political problems. That must stop, says Lesotho's Foreign Minister, Motsoahae Thabane.

"We do not need western countries to tell us how to solve our internal problems. They should assist us by injecting money to facilitate resolution of our problems without telling us how to go about it. We are ready to solve our problems." NEPAD and the G8

And some world leaders are heeding the call. Canadian Prime Minister Chretien has been extremely enthusiastic about NEPAD. At an April speech to the OAU in Ethiopia, he spoke of the initiative as a landmark document. "The millstones of despair that have weighed down the people of Africa for too long will be lifted," he vowed.

Chretien also promised to put African concerns front and centre at the June G8 meetings in Kananaskis, Alberta. The G8 summit will propose new directions for the relationship between the world's most powerful nations and Africa. Any changes could make a big difference, as the G8 group of industrialized nations contribute over 70 percent of Africa's development aid.

Increased aid is certainly needed. Overall, aid to Africa has plunged from $19-billion a year at the start of the 1990s to $12-billion today, a per capita drop of 40 percent. Most major donors, including Canada, are falling far short of the goal of 0.7 percent of GNP for aid. In fact, the overall level is now only 0.22 percent. That's only one-fifth of the level provided to Europe under the Marshall Plan. Per capita aid to sub-Saharan Africa plunged sharply in the second half of the 1990s, from $34 to $20

At the same time, debt remains a millstone for Africa. The continent has to spend almost U.S. $15-billion per year repaying debts to G8 countries and international financial institutions. This makes it extremely difficult to address urgent domestic needs. For example, debt payments devour 35 percent of Tanzania's national budget. The government spends nine times as much on debt repayment as on basic health care and four times as much as on primary education.

Some argue that cancelling debt would be more helpful in both the short and long term than NEPAD.

There are some hopeful signs. Britain has appealed for a doubling of aid levels from $50-billion to $100-billion. Canada is setting aside $500-million (Canadian) as a special fund for NEPAD. While our development aid has sunk steadily to only 0.22 percent of GDP, the Chretien Government has recently offered to increase aid by 8 percent per year over nine years, which would bring it up to about 0.4 percent.

At a March meeting of leading industrialized countries in Monterrey, Mexico, the European Union committed to raising its overseas development aid from the current level of 0.33 percent of GNP to 0.39 percent by 2006, when the U.S. will also be giving an extra $5-billion a year.

And a recent G8 Finance Ministers meeting held in Halifax, Nova Scotia in June - precursor to the full G8 summit in Kananaskis - recommended reducing debt of the world's poorest countries (mostly in Africa) by $1-billion. The meeting also endorsed over $4-billion be earmarked for health and education. While welcomed, many development agencies say these pronouncements don't go far enough. And past G8 promises have not always been honoured.

Greatly increased aid levels, to the tune of $64-billion per year, are needed to achieve NEPAD's ambitious goals, claim African leaders. As the African Capacity Building Foundation notes, "the resource mobilization challenge is enormous."

Yet G8 leaders have already poured cold water on prospects for aid volumes of that magnitude. "If people believe NEPAD is suddenly going to produce $64-billion they may be disappointed," said Robert Fowler, Prime Minister Chretien's personal representative for the G8 summit.

However, G8 countries are attracted to the NEPAD initiative for some compelling reasons. They realize that Africa's poverty and marginalization threaten global stability and well-being. Supporting NEPAD also enables G8 nations to defuse some of the powerful anti-globalization sentiment of recent years.

And increased prosperity in Africa can help the G8 nations. Africa's 700 million people can become, in time, a good market for the products of G8 countries. As Chretien bluntly told a May news conference:

"It is not charity, it's an investment. Because if you take somebody who is very poor and you make that person less poor, then he becomes a consumer of goods and services from the developed world."

And that's exactly what some people are worried about.

Does NEPAD Go Far Enough?

The Africa-Canada Forum of the Canadian Council for International Co-operation says that NEPAD represents a top-down approach to development, not one that grows out of the concerns of the poor and out of debate among African citizens. It is geared to Northern donors and a World Bank style of development, rather than calling for fundamental reforms of global trade and investment.

These criticisms call into question issues of power, and whether the plan will in fact be a true partnership. Prime Minister Chretien boasted in his speech to the OAU, that "We will be partners in every sense of the word. It will be a two-way street, with reciprocal and integrated obligations."

But who are the "we" referred to by Chretien? The plan may be by Africans, but for which Africans? Many feel it only refers to the leaders of the continent's wealthier nations, such as South Africa and Nigeria, who are NEPAD's most vigorous supporters and who are likely to receive the most investment dollars. Many feel that women, youth and other members of society have been largely left out of the NEPAD process. "Development in Africa cannot succeed without the full participation of all members of civil society," warns World Vision Canada.

"People don't know about it," Bayowa Adedeji told the Sustainable Times. A media liaison officer for the Nigeria's Centre for Human Rights, Research and Development, Adedeji has been in Canada helping with CUSO educational work leading up to the G8 meetings. "I was in Ghana for a month and nobody knew about it. Meanwhile (South African president) Mbeki is gallivanting all around the world talking about it." Civil society organizations are closest to the people at the grassroots, he adds:

"If we knew about this NEPAD plan, we would have debated it, and gone to the villages about it. Any scheme you bring, and you don't consult us about, is already a failure. We start wondering: why the secrecy?"

Dr. Molefe Tsele, General Secretary of the South Africa Council of Churches, spoke for many Africans when he attended the UN International Conference on Financing for Development in Monterrey during March, 2002: "We want to caution our leaders never to build the success or failure of [an African] recovery plan on the support they receive from the donor countries. We call on them to do their homework at home amongst African people first. They must assess what they can generate from their people, poor as they may be. They must take their people seriously, sell the concept amongst them before they travel capitals of the world parading project proposals for their dream.

"We are saying to our African leaders, the recovery of Africa is an African business. Work with us. We will determine when and how the donors will get involved. To that end, the New Partnership for Africa's Recovery, NEPAD, is premature. It is a partnership with African leaders without African people."

Others echo these concerns. "Without participation there can be no real partnership and no real development," says Neville Gabriel, a justice and peace worker for South Africa's Catholic Bishops.

What About Women in Poverty?

NEPAD has been sharply criticized for its lack of attention to women's concerns by people such as Mary Margaret Issaka. She's director of the Centre for Sustainable Development Initiatives in Ghana, which promotes access to education for girls, and other ways of helping women to overcome poverty and gain greater control of their lives. Supported by CUSO, she's currently working in Canada for several months with the Africa-Canada Forum of the Canadian Council for International Co-operation.

With over 25 years of community development experience under her belt, Issaka has grown tired of development initiatives that pay only lip service to the needs of women, who make up over 50 percent of the population in most African countries. "We are in neck-deep in the issues around poverty reduction, yet we are not consulted," she says.

In her eyes - and those of many others - NEPAD is yet another example of this sad process. "If NEPAD is to be implemented, great changes have to be made to it to include our ideas, our ways of doing things. Having worked with rural women for a long time, I have seen how they know what they need and how to get it. They are so clever. Give them the skills and they will come up with what is beneficial for them."

What's needed, says Isaaka, are the resources so that the NEPAD plan can be taken to these women and tailored to meet their needs. Issaka helped promote a resolution to this effect that was approved at a recent Montreal meeting of 130 African partners and 400 Canadians. It urged CIDA to help fund workshops and seminars in Africa to educate people about NEPAD, the issues it raises, and seek their ideas about it.

"Women have been left far behind," says Isaaka. "It's not too late. They should still bring us into the picture."Trade Rules Punish Africa

Others doubt whether NEPAD's corporate-oriented model of trade liberalization will work for all of Africa. "NEPAD correctly states that current globalization policies fail to lift Africa out of socio-economic decline, but then goes on to say that Africa therefore needs more of the same policies," says Mongezi Guma of the South African Council of Churches.

Most people would argue that investment and trade are important for Africa. But NEPAD's ambitious goals cannot succeed without changing the unequal terms of trade enforced on Africa. Seventy percent of Africa's exports are unprocessed raw commodities (Peanuts, Coffee, Tin, etc.), and most commodity prices have been falling. That helps explain the sad fact that while Africa generates nearly 30 percent more exports today than in 1980, their value has plunged by more than 40 percent due to falling terms of trade.

Oxfam slams the way that world trade rules punish African nations in a recent report, noting that a mere one percent increase in Africa's share of world exports would generate $70-billion (U.S.) - about five times what the continent receives in aid.

"In their rhetoric, governments of rich countries constantly stress their commitment to poverty reduction," Oxfam notes. "Yet in practice rigged rules and double standards lock poor people out of the benefits of trade, closing the door to an escape route from poverty."

When developing countries export to rich-country markets, they often face tariff barriers four times higher than those faced by rich countries.

It's also true, however, that trade barriers within African countries themselves remain high and crimp economic growth. NEPAD wants to lower them.

Specific elements of NEPAD's recipe for development have come under fire as well. The plan should pay much more attention to the AIDS epidemic that has ravaged the lives of millions of Africans, argues Dr. Chinua Akukwe from the Washington-based Constituency for Africa.

"The HIV/AIDS epidemic is unarguably the greatest threat to Africa's development at this point in time," Akukwe says. In the hardest hit African countries, the epidemic is directly responsible for annual loss of 0.5-1.2 percent of GDP.

Africa on the Agenda

Despite these criticisms, the New Partnership for Africa's Development represents an opening - a chance to broaden the discussion to so that it truly promotes the kind of development that will benefit Africa's majority population.

Moreover, simply getting Africa onto the G8 agenda and into public awareness, is itself a major achievement. Even NEPAD's critics concede that this represents a major advance. As Mary Margaret Isaaka notes, "At least it's put Africa on the world map." The days of ignoring Africa, until the next famine or other disaster, are hopefully over.

Perhaps Thabo Mbeki's talk of an African Renaissance may not be so far fetched after all.

Note: Please check the updates section below after June 30th for a report on the completed G8 meeting in Kananaskis.

Murray MacAdam is a Toronto-based writer specialising in community development and global issues.

Written June 2002.

| Return to Top

|

| Articles Archive

| About Our Times |