Foggy Weather, Bright Future

by David Napier

|

Navigating the narrow dirt road that winds its way through the coastal mountains of north central Chile toward Chungungo is like riding a giant snake. Driving this route at night is simply frightening.

The absence of guardrails between my tiny rental car and the pitch-black abyss is unnerving, but it's the small white crosses that light up like ghosts in front of the headlights that make me sweat. Having travelled before in Latin America, I immediately recognize these wooden roadside markers as crude memorials to those unfortunate drivers who lost control of their cars and trucks and plummeted to their deaths.

The steering wheel grows moist as I decelerate to a snail's pace. Eventually I pass El Tofo, an abandoned mining town at the 780-meter high summit, before descending to the fishing village of Chungungo. Only there do I breath a sigh of relief and wait for sunrise.

And daybreak illuminates a remarkable sight: the work of a Canadian-led team of "cloud physicists" who have adapted centuries-old technology and brought water to this rustic outpost, one of the driest places on earth.

The drought here ended when Bob Schemenauer, Emeritus Research Scientist with Environment Canada, teamed with the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Pilar Cereceda, a professor at the Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, and Chile's national forestry department.

Together they established the world's first modern fog collection program in this sleepy town 600 kilometres north of Santiago.

Residents of Chungungo survive on the fish they haul from the Pacific Ocean, and traditionally got their drinking water from a truck that made sporadic trips to the community. But it only left each person with a paltry daily ration of 15 litres - a scant amount compared with the 330 litres that the average Canadian consumes a day.

"Up until 20 years ago, Chungungo received water from the iron mine of El Tofo," says Schemenauer. "But when the mine closed, water was trucked... from a well 40 kilometres away. The water delivery was irregular, the water not of the best quality, and the cost high."

All that changed in 1992.

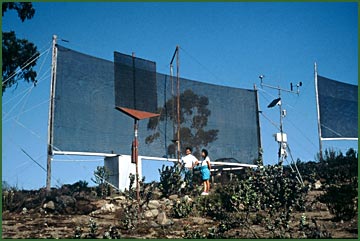

Building on principles of moisture collection that are thousands of years old, mesh nets, whose tops are six meters above the ground, are stretched between two posts on the hilltop overlooking the town. As clouds pass through what look like 94 oversized volleyball nets, beads of water run down the polypropylene nets into gutters.

The net result is an inexpensive and abundant - as much as 15,000 litres of water a day - source of fresh water for both domestic and agricultural uses.

Fog collection is based on the centuries old, simple tradition whereby the leaves of trees and plants trap droplets from coastal clouds for thirsty yet resourceful people.

In Chungungo the immediate results were striking, both in terms of the increase in water and its effect on the local community. The number of residents in Chungungo jumped to 400 after the fog collecting nets were raised on the nearby mountain.

"People used to leave the village and head for the big cities because there was no water and therefore no hope. Now people have a reason to stay," says Schemenauer, who has helped set up similar operations in such arid spots as Oman, Nepal and the Baja Peninsula, Mexico.

"Before there were only a few trees, no plaza, no gardens and no one had crops," says Professor Cereceda of the situation in Chungungo. These days villagers grow their own herbs and prepare meals that include fruits and vegetables rather than just seafood. Flowers have been planted, clothes are washed in clear water, and modernity hit town in the form of a gas pump located near the central plaza.

But for all the promise of the project, based largely on international support from the federal government of Canada and a handful of generous Canadian citizens, the project at Chungungo has unfortunately faltered in recent years. Development doesn't happen overnight.

"We gave responsibility [for operating the collection program] to the town," says Cereceda. However, the nets have not always been maintained nor the water collection systems kept clear and clean. Leaves often clog the collection pipes.

The trouble started when the IDRC did what it always said it would and turned off the tap on funding in the late 1990s. They didn't want to create a long-term dependency on external money.

At that point, interest on the part Chungungo residents seemed to run dry.

The technology is relatively simple, but by local standards costly to operate. The major problem, though, is labour.

Survival can be difficult here, like in most corners of the Third World. There isn't always free time for broader volunteering. "So if people don't get paid they don't come here to clean [the fog collectors]," says Pato Piñones, director of the Water Committee of Chungungo, standing beside a water tank that is dangerously close to empty.

He points to massive concrete water tanks with a capacity of 600 cubic meters that on this day holds less than 35 cubic meters. "Normally it would be full," says Piñones. "What's here is only enough for half the village, for two days."

Piñones single-handedly cares for the nets and four holding tanks where the water gets stored. He has been head of the Water Committee for four years (two years longer than he planned to hold the post) and a member of the Committee since it was conceived, seven years ago. He believes the project will survive, and that fog catching can be a solution for other communities suffering from drought.

When I ask if he'd rather live in Santiago and raise his three children there, Piñones admits it would be nice to make a decent wage and be appreciated for his labour, but quickly adds that this is his home. And he is needed here.

'Here' is a mountaintop overlooking a tiny maze of dirt roads that separate the ramshackle houses of Chungungo. The view is stunning. After the morning fog has lifted, one can see the blue-green Pacific Ocean dotted with a handful of fishing boats. The crew on these distant vessels are men that Piñones knows well. They are hearty souls who will not break with tradition: they search the vast expanse of a salty sea for sustenance.

They know where there next meal will come from, but what about their next glass of water?

On the top of a mountain overlooking their village, Piñones just may have the foggiest idea.

David Napier is a Halifax-based writer.

Written September, 2001

| Return to Top

|

| Articles Archive

| About Our Times |