|

Coffee is the world's favourite stimulant - Canadians alone drink 15 billion cups each year. It's a very profitable business, yet many coffee farmers live in poverty. But thanks to a growing fair trade movement, consumers can now put their ethics where their mouths are. |

Genaro Jimenez Hernandez, not Juan Valdez, is the face behind your morning fix. The Mexican farmer grows coffee in the lush jungles of Chiapas. It's a hard life, and hard to make a living.

The next time you savour a cup of joe, consider this: the farmer who grew those beans may have received less than one-tenth of the price you paid. But thanks to a coffee-selling co-operative in Nova Scotia, Canada, Hernandez is harvesting a better life for his family.

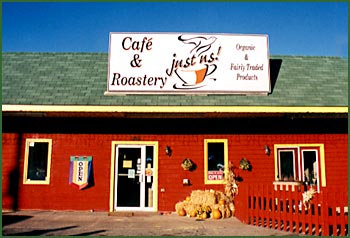

Nestled in Nova Scotia's Annapolis Valley, business is booming at Just Us! Coffee Roasters Co-op. Debbie and Jeff Moore, David and Jane Mangle, and Ria March formed the co-operative in 1996. They buy organic, unroasted beans directly from Mexico, roast it themselves, and sell it throughout Atlantic Canada.

Just Us! began after Jeff Moore travelled to Mexico in 1995 where he visited several coffee farmer co-ops. On his return to Canada he decided to sell organic coffee purchased from Third World farmers at a fair price.

After contacting Union de Ejidos de la Selva (Union of the Forest), a 1,350-member co-op already supplying European 'fair-traders' with green organic coffee beans, the match was made.

Over ten tons of beans followed.

All five members of Just Us! invested much of their life savings - the Moores even mortgaged their house. They also received a loan from the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency, a federal development funding body. The money allowed them to pay for the coffee and a roasting machine, and to set up a small cafe and roastery.

So far the risk has been worth it. The members of the coffee co-op probably need the caffeine just to keep up.

Two years ago, the co-op's sales to wholesale and retail markets throughout the Atlantic Provinces averaged $55,000 per month. Today they are serving up over $100,000 in business monthly. You can now buy their fairly traded, organically grown coffee throughout the region at cafes and supermarkets such as Sobey's and IGA.

Making shrewd use of guerrilla media tactics has helped offset a small advertising budget, says Moore. Sponsoring a tour of coffee farmers from Mexico to Canada sparked media interest "that was just magical, " he recalls. "It really put us on the map."

Yet Moore credits an insistence on quality and hard-nosed business smarts as key factors behind the success of Just Us! "We take a business approach to fair trade, not because we're greedy, but because if you don't make money, in the long run you're not going to do anybody any good, " says Moore.

The co-op cracked the supermarket market because it offered top-quality coffee at a competitive price. "We've focused on the best product we can put out."

Back at the co-op, David Mangle watches the roaster's temperature gauge closely. 340 degrees...350...360. Mangle checks his clipboard on when to ease the flame. "If you go too quickly you'll lose flavour, " he explains.

He waits until 390 degrees and adjusts the flame. The temperature stabilizes. Twelve minutes and 40 seconds after the beans were dropped in, Mangle releases them, steaming, into a large pan. A few degrees hotter, they would have been scorched.

"Brown, with just a hint of smoke," he says, "it's a good batch."

Just Us! customers certainly like the taste of the coffee, but they also appreciate the fact that it's pesticide-free. "We know where our beans come from, " explains Mangle.

And because the co-op buys directly from the farmers, a greater share of their coffee's retail price reaches the people who actually pick, peel and dry the beans.

While the four or five dollars a day that farmers like Hernandez and his family get paid is not a lot for picking and preparing raw coffee - exhausting work in hot, humid weather and difficult terrain - it's often ten times as much as what their neighbours make working for the pesticide-intensive coffee plantations.

It's also a better deal than what other independent growers can receive when they sell to the brokers out to profit from fluctuating world markets. Commodities markets are notoriously volatile - speculation leads to wild price swings, and drought or frost in any of the major coffee-producing countries (Brazil, Colombia, Indonesia and Mexico are the biggest) can dramatically affect global prices for the 16 billion dollar industry.

But throughout the ups and downs, the cost of a cup at Tim Horton's doesn't change much.

"The fact that we trade directly with buyers is very important to us," says Hernandez. "This helps us skip the intermediaries, the 'coyotes' - the brokers that resell the coffee and take such a profit."

Fifty-five percent of the money made from coffee goes to shippers and roasters, 25 percent to retailers, 10 percent to exporters and 10 percent to the actual growers. A fall in commodity prices hits farmers hard. A Dutch community worker who helped the Chiapas co-op says price drops combined with poverty sometimes drives into the arms of the coyotes.

"Brokers try to get into the community and deal directly with individuals," says Jeronimo Pruijn. "They are taking advantage of the [sometimes desperate] needs of a family."

For many years, the market price for green coffee hovered around 90 cents U.S. a pound. Today, the price of coffee is at its lowest level in decades - about 50 cents U.S. a pound. With development organizations such as the World Bank pushing coffee as a quick fix for Third World poverty (or to pay interest on debt), over-supply has caused prices to tank.

But farmers selling coffee to businesses licensed by Trans Fair Canada, an Ottawa-based company supported by labour and church groups, have always received, and continue to receive, a minimum of $1.26 U.S. per pound.

Most big players in the coffee business - for example Nestle, which buys 12 percent of the world's unroasted beans - refuse to pay the fair trade price, instead relying solely on world commodity markets to set payment.

And coffee companies are making big bucks. Nestle netted over $1 billion in profit from its beverage division last year, and predicts 20 percent profit growth this year. As they said to their shareholders: "Profits increased and margins improved thanks to favourable commodity prices."

There's a lot of money being made, but it's not trickling down to the estimated 20 million Third World households dependant on coffee production, many who live in absolute poverty.

That's why Just Us!, a Trans Fair Canada partner, pays the Union de Ejidos de la Selva co-op a minimum price of $1.26 U.S. a pound, even when coffee prices drop. Farmers are also protected if the price goes up; Just Us! commits to paying $0.05 U.S. per pound more than the world price - $0.15 per pound more for organically grown beans.

This means Just Us! coffee can cost a bit more in Nova Scotia. (The co-op also has to struggle with the low Canadian dollar.) But that's one of the accepted principles in fair trade: when they do business with Chiapas, the grower is placed on an equal footing with the consumer.

That price difference adds up.

Another farmer, Bertilda Gamez Peres of Nicaragua, sells her coffee to European markets on a fairly traded basis. "We didn't make enough to live on before," she says. "Now we get a better price and the money comes directly to us. I can buy more food, I can help support my daughter at university and take care of my son."

>Fair trade is still only a small fraction of the overall global trade, but it can have a big impact on the lives of farmers on the ground.

The alternative trade movement is creating a buzz the world over. Groups such as Equal Exchange and Peace Coffee are brewing up sustainable coffee in the U.S., while many fair traders have set up shop in Europe. In Switzerland, fair trade coffee has captured 5 percent of the market. It's 3 percent in England, and 2 percent in Holland.

In Canada, you can't yet walk into just any supermarket and pick up fairly traded coffee along with the rest of your groceries. But it could happen soon - a growing number of Canadians consider themselves ethical shoppers and are willing to pay more so producers can enjoy a living wage.

A 1998 survey by the CROP polling firm found that 55 percent of the 3,000 consumers questioned said they would pay 15 percent more for a package of coffee if it carried a label saying it was produced under conditions respecting human rights.

Trans Fair Canada already licenses 30 fair trade suppliers, which together sells 100,000 kilograms of coffee.

While that's only one-tenth of one percent of the overall market share, this figure is rising.

A harsh truth remains, however: fair trade, despite impressive growth, is but a bit player in an unequal global economy. "Fair trade reflects all the contradictions of the societies we live in," says Bob Thomson, former managing director of Trans Fair Canada.

"Fair trade makes a concrete difference and is one very small way of showing that there are alternatives that are viable. It is constructive in the eyes of many consumers. But because it doesn't tackle the root causes of global economic inequity, it can only be a 'necessary but not sufficient' condition for change."

But fair trade businesses are helping consumers put their ethics where their wallets are.

"People in Canada need to understand the real costs of what they purchase, both ecologically and socially," says Dwayne Hodgson, a Canadian who has worked in community development in Tanzania.

"The notion that we can't afford to buy fair trade products needs to be turned on its head. By preferring 'unfair' products, we are contributing to injustice and ecological degradation."

"That's a tough message to market, but it gets to the root of the issue." And that's definitely something to chat about over coffee.

Perhaps Just Us! is a success story because Nova Scotians love good coffee, even if it means spending a little more.

Or perhaps it's also because an increasing number of Canadians want to spend their hard-earned dollars on sustainable and ethical products.

Hudson Shotwell, owner of the Trident café in Halifax, says he bought up the Just Us! coffee for an expresso blend when he first learned of it. After a trip to the co-op to see the operation, he has worked Just Us! coffee into five other blends he serves. While he initially switched over for business reasons, he says the coffee's taste and fairly traded, organic nature has grown on him, and his customers.

"It's almost like a win, win, win, win situation," he says. For many reasons, Just Us! makes a good cup of coffee.

Adapted from original articles for the Sustainable Times by Murray MacAdam and David Redwood.

Updated January 2002.

| Return to Top

|

| Articles Archive

| About Our Times |