Bankrolling the Future

Is Microcredit the Solution?

By Sean Kelly

For the world’s poor, getting a business loan can be next to impossible – they simply don’t have the collateral the banks demand. So a growing ‘microcredit’ movement is giving them a hand-up, not a hand-out. But is it a panacea to poverty?

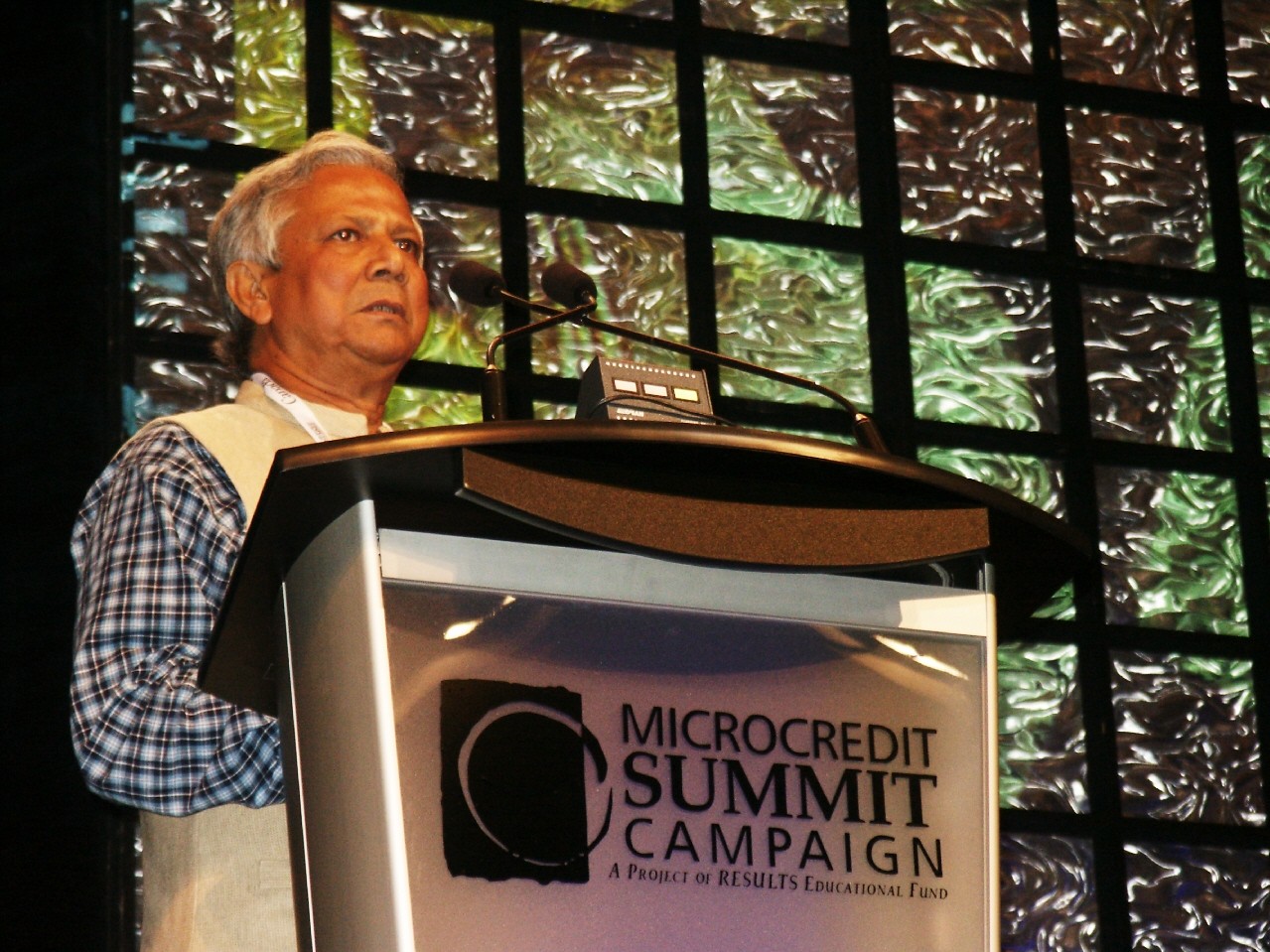

Addressing a large crowd of development workers and anti-poverty advocates from around the world, the modest Bangladeshi economics professor – who also happens to be the most recent winner of the Nobel Peace Prize – allowed himself a small ‘I told you so’ moment.

“Those who ridiculed us, who ridiculed the idea of giving loans to the very poor, are now jumping onboard,” Muhammad Yunus told delegates gathered for the opening ceremonies of the Global Microcredit Summit, held November 12-15 in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Microcredit has indeed become a growing phenomenon, no longer micro in its reach. Thousands of organizations have lent billions of dollars to well over 100 million people, the majority being the so-called ‘poorest of the poor’. Most of these are women.

The lending scheme is a development tool that offers a hand-up, not a hand-out. It’s a way to provide small business start-up capital – often $100 or less – to people who don’t qualify for traditional bank loans because they have no collateral or credit history. An amount that small may not seem like a lot, but for someone living on the edge of survival, it’s enough to kickstart a micro-business selling food or crafts or telephone calls to people without phone service.

In most programs, groups of people form lending circles, and act as each other’s collateral. If one fails, the collective carries the loss. It’s a simple yet powerful idea. Without access to capital, it’s difficult to start or expand a business, even the tiniest of operations. In the absence of alternative banking options, many people are forced to borrow from money-lenders who charge outrageous interest rates. The poor can get trapped deeper in the pit of poverty.

Microcredit was popularized – but not created, as earlier initiatives can be traced to South America – by Dr. Yunus and the Grameen Bank, which he founded in 1976. It all started when he lent a few dollars from his own pocket to a group of poor artisans struggling to make ends meet. They had no savings, and to buy the supplies needed for their wares, they had turned to a loan shark. At the end of the day, their hard work amounted to mere pennies.

But because of the good professor’s investment of about a buck-and-a-half each, the 42 enterprising street vendors dramatically increased their profit margins. And all the ‘micro’ loans were re-paid. An idea was born.

These artisans became the first borrowers of the Grameen Bank (grameen means rural in Bengali), which today has seven million clients, helping over 30 million family members. Grameen – like all microcredit programs – is built on the belief that the poor are not poor in all aspects of their lives. They may not have money, but they have pride and unique survival skills that can serve them well in the realm of business.

Sam Daley-Harris is the Director of the Global Microcredit Summit Campaign, and founder of Results International, a leading proponent of small-scale lending. He believes microcredit is nothing less than a “revolution in banking.”

“When banks only lend to rich people, microcredit loans go to the poor. When banks lend primarily to men, microcredit loans go to women. When banks demand collateral, these loans are collateral-free. When banks require paperwork, the microloans are illiterate-friendly. It’s banking that breaks rule after rule.”

But is it banking that reduces poverty? Because of its history in microcredit, Bangladesh is a litmus test of the concept.

In 1974, then-U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger called Bangladesh a “basket case.” Now, 32 years later, and 30 years since the first micro-loans were made by Dr. Yunus, Bangladesh has overtaken India – the region’s leader in modern economic development through globalization – in reducing child mortality rates. If India had matched Bangladesh’s rate of reduction in mortality, 732,000 fewer children would die this year. A 2005 United Nations report argues that the country has become the regional leader in reducing poverty.

Is this progress the result of the many microcredit organizations that have reached 21 million clients through small-scale lending, affecting 105 million family members in a country of 140 million? There are many reasons for the steps forward, but a multi-year study by the World Bank concluded that microcredit alone accounted for 40 percent of the reduction of rural poverty in Bangladesh. Three percent leave extreme poverty each year because of microcredit.

This success story has been heard around the world, and the microcredit model is bankrolling hopes in Asia, Africa, Central, South and even North America.

But the poor are not one homogeneous group. Microcredit can’t help everyone lift themselves up by their bootstraps. For some people, just getting those metaphorical boots is the struggle.

Konlan Lambongang is the executive secretary of Maata N Tudu, a microcredit organization and CUSO partner group based in Tamale, in Northern Ghana. The group – whose name translates as Women of the North – has around 7,000 members. Lambongang was in Halifax for the summit, and admitted that it’s a challenge to help the poorest of the poor.

“For some people, you might need grants at first so they can just survive, so they can just eat and live. They need to get themselves healthy enough so that they can make use of the loans, and have the ability to pay them back. We are actually reaching the entrepreneurial poor.”

But if the participants didn’t have to pay back the loans – or even the interest – they would be able to keep more of their hard-earned money. And that would help their families even more. So why not give grants instead? Daley-Harris of the Global Summit Campaign has a simple answer. “If I give you a hundred dollars for you to start a business, I then have to find another hundred dollars to help the next person. But if I lend you that hundred dollars and you pay it back, that becomes money that circulates through the community and helps many more people.”

And a lot of money is circulating as microcredit loans. There is around US$4.5 billion worldwide committed to microcredit, a sum that’s growing 20 percent each year. The scheme is being funded by international donors such as the World Bank, foreign aid agencies, financial institutions, social investors and the participants themselves.

There are, however, concerns that microcredit is becoming a First World-driven model, with the accent on recoupment of investment. That’s why Yunus believes future funding must come from the ground up. “We must build up local savings, so microcredit is not dependent on international donors. We don’t want to have to wait for their money, or be dependent on their regulations. Not that we aren’t grateful for their assistance.”

And, he argues, microcredit must not become a primarily commercial venture. “This is not about profit – it must be about how many people leave poverty. That is what we must measure, that is what we must count.”

A lack of credit is not the only cause of hardship in the Developing World. Many factors contribute to under-development, and microcredit is not a panacea to poverty. The resources devoted to it might be better spent on other approaches; but while we muster the political will to act, the world’s poor can’t wait.

Providing business loans may or may not be the best way to lift them out of poverty. Yet the appeal of microcredit is that it offers women increased independence today, not tomorrow. It helps get kids to school today, not tomorrow. It bankrolls community development today, not tomorrow. And when tomorrow does come and the loans are re-paid, that many more people will get credit, where credit is due.

Written January, 2007

Sean Kelly is a writer living in Prospect, Nova Scotia. He works with CUSO, a Canadian non-profit international development organization.

| Return to Top

|

| Articles Archive

| About Our Times |